In the aftermath of Lindsey Vonn's crash, it's natural to wonder whether she took on too much risk. It's a question many Olympic athletes have to ask themselves.

LIVIGNO, Italy — In the aftermath of Lindsey Vonn’s crash Sunday in the Olympic women’s downhill, it was natural to wonder whether she took on too much risk by skiing with a torn anterior cruciate ligament in her knee.

But for many athletes at the Milan Cortina Games, particularly those who compete in sports that would be inherently dangerous for regular people, the entire concept of acceptable risk isn’t relatable at all.

“In a lot of ways, it’s kind of like driving your car,” said retired ski racer and four-time Olympic medalist Julia Mancuso. “It’s supposed to be safe but there’s car accidents all the time.”

While the outcome of Vonn’s decision to compete played out in horrifying fashion for everyone to see — to be clear, it’s uncertain whether weakness in her knee or an over-aggressive strategy caused her to clip a gate and go tumbling toward further injury — the unfortunate result does not inherently mean she was reckless.

In an array of winter sports that take place on snowboards and skis, typically involving human beings moving down a mountain at top speed or spinning and flipping through the air, there is no competition if there is no risk.

The athletes who have chosen to make those sports their life’s work face the potential of severe injury and death every day. But that does not mean they approach competition with fearlessness. Often, it’s quite the opposite.

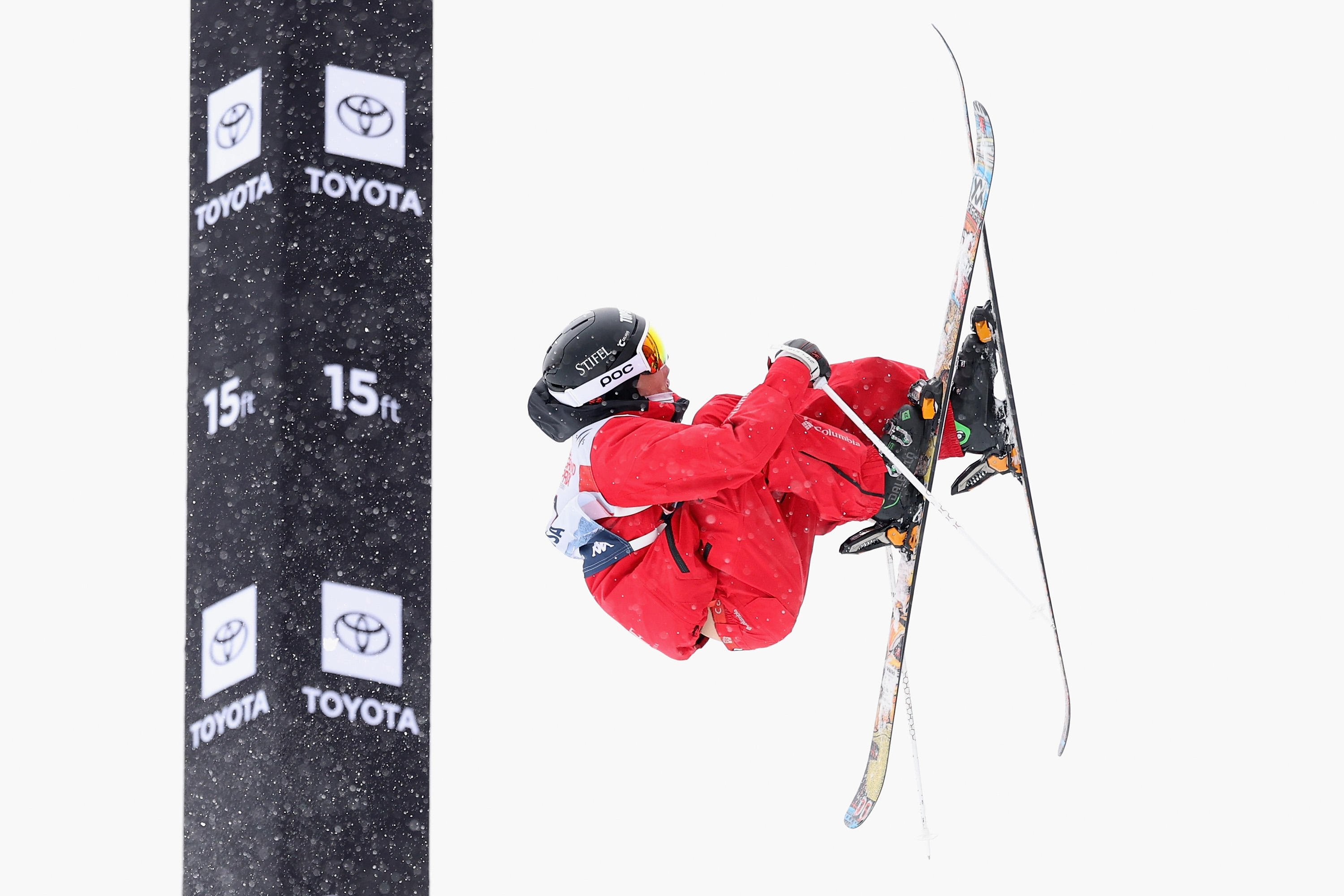

“You’re about to fly through the air with these heavy sticks and weights on your feet and you’re going to take off on ice and land on ice,” said Alex Ferreira, a freestyle skier who specializes in the halfpipe. “And if you don’t do it perfectly, the consequence is extremely high.”

Ferreira, a 31-year old who won a silver and bronze medal at the last two Winter Games, does not fit the outdated stereotype of an X Games athlete rolling out of bed after a night of partying and hitting the mountain in baggy pants. Maybe some of that was true in his younger days, but as one of freeski’s elder statesmen, he’s in bed by 8 p.m., brings his own food on the road and approaches his job with extreme seriousness.

That’s because the job is to launch himself into a curved, hollowed-out icicle with 22-foot walls, ski up the sides and use the momentum to get airborne. From there, he will perform complex, highly technical tricks that get bolder and more dangerous every year to remain competitive in a sport where each generation of athletes pushes past old boundaries.

A bad day at the office doesn’t mean failing to medal. It’s broken bones, as Vonn suffered on Sunday, concussions and maybe even a loss of life.

What is going through Ferreira’s mind when he’s getting ready to drop in and perform some of these tricks, particularly ones he’s never tried in competition? It’s not fearlessness. Sometimes, it’s quite the opposite.

“I’m scared ****less,” he said.

Knowing your limit

But for the best in the world, a healthy respect for the worst-case scenario isn’t just a requirement, it’s a superpower.

It never guarantees that everyone is going to make it through safely. But it does tilt the risk profile further in their favor than most of us civilians can wrap our minds around.

That can be hard to quantify with a number, but it’s the seed of doubt that keeps them safe on days when the wind blows a little too hard or when they’re not physically at their best. It’s the meter in the back of their minds constantly calculating the likelihood of landing a trick or nailing a run — and the potential danger waiting for them if they don’t. In many cases, it’s what prevents a bruising fall from becoming broken bones or worse.

It’s the necessary boundary between being an adrenaline junkie and doing something that turns risk into recklessness.

“I’ve never tried anything where I was like, ‘Oh, this might not be the day for it,’” said Alex Hall, the freestyle skier who won slopestyle gold in Beijing four years ago. “You want to be on the upper edge of your comfort level, but there’s a fine line between (approaching it) and going beyond it.”

Did Vonn go too far?

Mancuso can only relate it to a similar experience she had at the Sochi Games in 2014, where her confidence after winning the first portion of the women’s combined event got the better of her and she took more aggressive lines than she should have in more difficult conditions.

“I think she went into the Olympics and was like, ‘This is it. I’m leaving it all on the line,’” Mancuso said. “And she kind of forgot she was injured. And rightfully so, you don’t want to go out of the gate thinking I’m injured. But in this situation, she probably shouldn’t have been pushing the limits above that line. It looked to me like the course ran faster and you could see her kick out of the start gate with everything she had to give and went really tight across the traverse.

“If you’re really trying to not leave anything on the hill, you cut the line to these tiny bits. So in that sense, she was really trying to be perfect and the snow was a little bit grippy or a bit harder and it didn’t push her down the hill probably like she thought and launched her right into that gate.”

Bar continues to rise

Much like in speed racing, where the improvement in technology has made skiers faster and their task more treacherous, the trend lines in freeski and snowboard have moved in the direction of more dangerous maneuvers. Tricks that might have won medals two or three Olympics ago are now considered pedestrian.

Take, for example, the big air competition. Added to the Olympics in 2018, competitors ski or snowboard down a massive ramp, launch into the air and perform a trick that is judged on a variety of factors including creativity, difficulty, number of flips and rotations and, of course, execution.

It is an inherently dangerous endeavor, one that has always given pause to Red Gerard, a slopestyle specialist who won the gold medal in 2018. In the Olympics, making the team means qualifying for both events automatically. After failing to qualify for the Big Air final on Thursday night here, he questioned why snowboarders have to do both and criticized the setup of the jump, a freestanding structure built on scaffolding, rather than cut into the mountain.

"I don't understand why we're forced to do this," he said. "I just want to be focusing on slopestyle. Not to dig on anyone that does it — everyone that does this are badasses that are very good at the sport — but this is not my gig."

Gerard is among the many snowboarders who watched as Canada's Mark McMorris crashed during big air training on Wednesday and withdrew, citing the fact he hit his head during the fall. Though it appears McMorris did not suffer serious injuries and could compete in slopestyle, it was one more factor giving pause to riders like Gerard who do not want to compromise themselves for their best event.

"He's like a GOAT of our sport," Gerard said. "You think those guys are invincible in a lot of ways and it sucks to see when it does happen like that. I think, personally, maybe that could have been avoided, doing a jump on scaffolding and stuff like that."

And Big Air only gets bigger and more dangerous every Olympic cycle.

Snowboarder Jamie Anderson, now 35, won silver at the first big air in Pyeongchang with a frontside 1080-degree trick — three full rotations in the air. She was one-upped by Austria’s Anna Gasser, who executed a more complex 1080.

Four years later in Beijing, it took a double cork 1260 — 3 ½ full off-axis spins — for Gasser to repeat as gold medalist while Anderson finished off the podium. Anderson, who failed to qualify for this year’s Olympic team after taking time away from the sport to have children, acknowledged that her new status as a mother changed her risk profile.

“The tricks are crazy,” she said. “Girls are doing triple corks and 1440s and maybe even 1620s. In four years to see how much it’s evolved and progressed just goes to show how insane all the training facilities and modern technology has become.”

No guarantees

These skiing and snowboarding labs are where the elaborate and dangerous tricks get built. Before one of these athletes ever tries something risky on the snow, they will have practiced all the moves on a trampoline, progressing to rollerblades into a foam pit and then jumping into a 300-foot by 100-foot airbag with their skis or snowboard on.

Still, even after months of development, it’s different when you’re on the mountain with no air bag for protection.

“You have to go, you have to try it and you have to fully commit the first time,” said Nick Goepper, a freestyle skier who has medaled in slopestyle at the last three Winter Games.

But what happens if you get into the heat of competition and realize everything you’ve practiced and perfected isn’t going to be good enough?

That may be part of what Vonn experienced Sunday, seeing Breezy Johnson post a run that was going to be tough to beat, forcing her to expand that risk tolerance just a little bit.

That’s certainly the situation Hall faced four years ago in Beijing, knowing he needed something special in his final attempt to medal in big air. Instead of trying an easier trick that would have given him a 50-50 shot to be on the podium, he took on extra risk trying to win it all.

“I didn’t make that decision until about five seconds before dropping in,” he said. “It didn’t quite go my way — I landed on my feet and barely tipped over — but I’m proud of trying it.”

In a way, that innate desire to reach for something a little more is what animates so much of the progression in these dangerous winter sports. It’s not just about winning, it’s about looking good and pushing your own limits — even if you fail.

“The guys you really respect in your sport, you want them to be excited about what you’re doing too,” Hall said.

As a result, it’s practically impossible to compete in these sports over a long stretch of time without suffering a few injuries along the way, forcing athletes to hone their own instincts about what’s too dangerous, how to safely eject from a bad situation and mitigate damage if something goes wrong.

“Once you take a crash, you learn quickly, ‘Oh, I don’t want that to happen again,’” Ferreira said. “You realize it can’t happen again or I won’t be able to keep going.”

But there are never any guarantees, and with each Olympic cycle, the bar for danger gets raised. Younger competitors are willing to take on more and more risk. The outgoing generation has to decide whether it’s worthwhile to try and keep up.

Vonn ended up on the wrong side of that line Saturday. But after a lifetime of managing the inherent risks of her sport, it wasn’t because she didn’t respect the potential for danger. It’s because she was comfortable with it in ways most of us will never understand.

Category: General Sports